Biography

Helene Koller-Buchwieser was born in Vienna on 26 November 1912 as Helene Buchwieser, eldest daughter of the architect and city builder Bruno Buchwieser, sen.. Early on, she had the desire to become a master builder, which she pushed through against her family’s reservations. While still at school, she worked as an apprentice bricklayer during the summer vacations. From 1932 to 1937 she studied architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Vienna, at the same time gaining practice as a construction technician and foreman on her father’s construction sites. As a construction foreman, she led repair work on the Romanesque church of St. Michael in Pulkau.

After graduating in architecture, she planned to continue her scientific education at the Technische Hochschule in the master school of Karl Holey, building historian and cathedral master builder. For this purpose, she had set out on a research trip to England, lasting several months, to collect materials on the development of university buildings of the Middle Ages. However, when she returned to Vienna at the beginning of March 1938, she was unable to continue her research because the National Socialist troops had invaded Austria and Karl Holey, at that time also rector of the Technische Hochschule Wien, could no longer remain in his position.

Helene Buchwieser quickly found an alternative and began working at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, which by this time had laid off many of its employees due to Nazi decrees and needed new ones to fill the now vacant positions.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum was the place where Aryanised and looted works of art belonging to Jews and other persons considered ‘hostile to the state’ were stored. The central depot of confiscated art was established on the second floor of the Neue Burg under the administrative and scientific direction of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. The works of art had to be housed, inventoried, and exhibited. This new area of responsibility had necessitated adaptation measures in the museum, which were subsequently to be implemented.

In order to implement these building projects, a building department had been set up in the museum specifically for this purpose, and Helene Buchwieser had become its head. Her tasks included the elaboration and supervision of ongoing construction work and architectural issues of the restoration, and the interior design of the Secular and Ecclesiastical Treasury as well as the Neue Burg. This included various construction works, such as installations, glazing, adaptation of the sanitary facilities, renewal of the passenger elevators, but also the supervision of the remodelling, e.g. of the Palais Pallavichini, in which the music collection had been housed. She was also responsible for organising the installation of the Hitler busts by Edwin Grienauer and Wilhelm Fraß, and for planning the decoration in preparation for Adolf Hitler’s visit to the museum in March 1939. While working at the museum, she met her future husband, the Austrian art historian Lothar Kitschelt, an illegal National Socialist in the early days and a member of the SS. They married as early as 1939, but this forced Helene Buchwieser-Kitschelt to resign from her position at the KHM, in accordance with the regulations for married women in the federal service.

Her political orientation is difficult to judge. She was not a party member and never applied for membership in the NSDAP.

In 1940, she returned to her father’s construction company as deputy plant manager, where she remained until 1948. In this capacity, at the end of the war, she was responsible for securing and reconstructing St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, deputising for the cathedral’s master builder Karl Holey, together with her brother Bruno Buchwieser, Jr. The restoration of war-damaged buildings also played an important role in their activities in the following years. On 16 May 1940, she was the first woman to pass the master builder’s examination, and in 1945 she obtained the title of civil engineer for structural engineering.

A war widow since 1944, she married Josef Koller, a section councillor in the Federal Ministry for People’s Nutrition, in her second marriage in 1947.

Before she became a freelance architect 3 years after the end of the war, she visited the USA for 6 months on a scholarship from UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) to study housing and settlement construction, new building methods and new building materials.

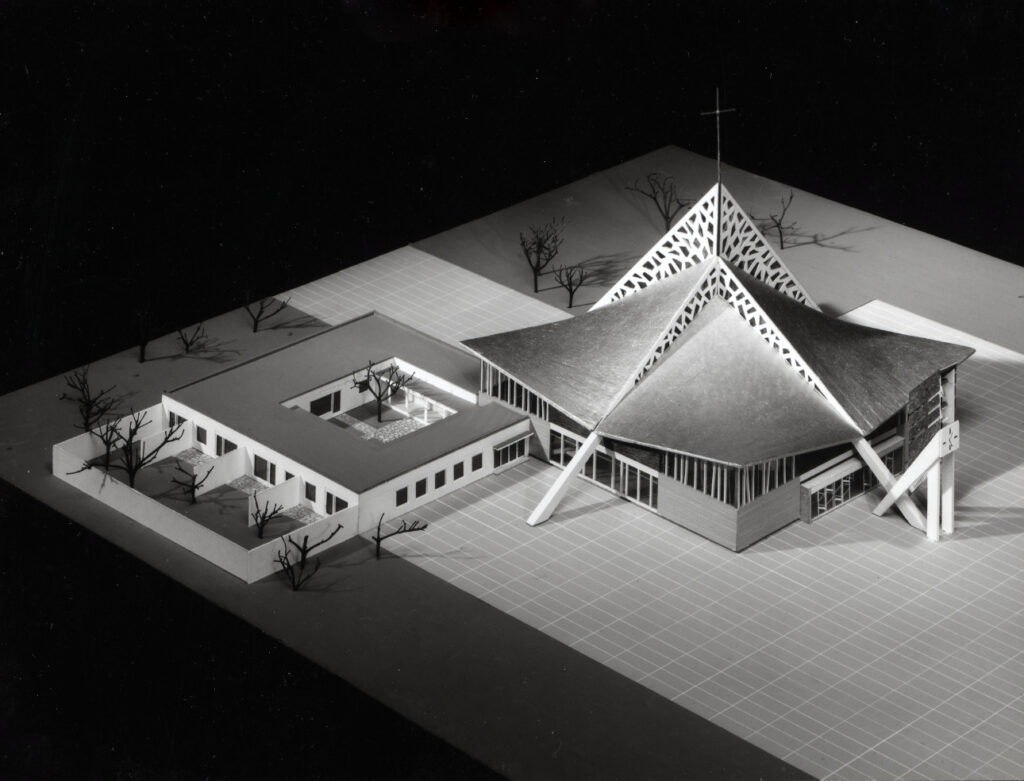

Since her independence in 1948, she had been able to obtain a variety of work assignments. In the course of half a century, Koller-Buchwieser planned and built with a focus on residential and sacred buildings, as well as educational buildings, administrative buildings and private houses. Among other things, she built residential complexes for the municipality of Vienna, housing estates, social housing, student dormitories and housing for the elderly, orphanages, schools, libraries, and factories. Helene Koller-Buchwieser successfully participated in national and international competitions, where she won first prizes for a school centre, a student dormitory, a children’s home, and a funeral home. Sacred buildings seem to have been a special concern of hers, which may have been due to her early work on churches and her family environment – her father was, among other things, a master builder for the Carmelite nuns. Thus, numerous churches and their outbuildings as well as extensions of convents were built by her.

In the later 1970s she was involved in reconstruction work in West Africa, for which she was even awarded the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice Medal of Honour by Pope Paul VI. As further honours she received the title of professor in 1979 and in 1988 the pin of honour of Hinterbrühl, the municipality in which she had her residence.

Helene Koller-Buchwieser left behind an extensive body of work. She was an architect and master builder and possessed the necessary art historical expertise for her work. Her great affinity for church architecture, as well as her social commitment, gave rise to important projects. She defined her lifelong goal as finding creative solutions to contemporary needs and giving architecture a spiritual dimension.

Works (selection)

Church buildings, ecclesiastical developers

1936 Restoration work on the parish church of St. Michael in Pulkau, Lower Austria,

1947 Restoration of the parish church of St. Leopold in Vienna 2,

1952 – 1956 Parish Church ‘zur Kreuzerhöhung” in Kittsee

1957 Reconstruction of the parish and religious church of Unserer lieben Frau vom Berge Karmel

1959 – 1961 Reconstruction of the ‘Waldkloster’ of the Kongregation der Töchter des göttlichen Heilandes (Congregation of the Daughters of the Divine Savior) in Vienna 10, Gellertplatz and boarding school, destroyed in 1945

Competition successes

1951 Design and realisation of residential buildings for the sugar factory in Tulln

1962 1st prizes for the school centre in Eisenstadt,

Children’s home in Kirchschlag in Upper Austria

1971 Buchfeldgasse dormitory for female students in Vienna 8

1977 Funeral home in Hinterbrühl

Housing estates for the municipality of Vienna

1958 – 1960 Gestettengasse 21a, 1030 Vienna

1959 – 1961 Tivoligasse 13, 1120 Vienna

For the young workers’ movement

1951 Young workers’ village Hochleiten-Gießhübl in Mödling (according to the pedagogical ideas of her brother Bruno Buchwieser, jun.)

Europahaus Vienna 14

Dormitory Bürgerspitalgasse Vienna 6

Further projects

Settlement Viktring-Klagenfurt

Settlement An den langen Lüssen in Vienna-Grinzing

1959 Studio house

1971 Slope housing estate Badgasse in Mödling

1970s Development work in the republic of Upper Volta, Africa: training centre for young people with boarding school. Church, community centre, student apartments, school of architecture

Sources

Juliane Mikoletzky, Ute Georgeacopol-Winischhofer, Magrit Pohl: Dem Zuge der Zeit entsprechend… / Zur Geschichte des Frauenstudiums in Österreich am Beispiel der Technischen Universität Wien. WU-Universitätsverlag 1997, p. 230f

Ute Georgeaocpol-Winischhofer: Koller-Buchwieser, Helene, geb. Buchwieser. In: Brigitta Keintzel/ Ilse Korotin, Wissenschafterinnen in und aus Österreich / Leben – Werk – Wirken, Böhlau Verlag Wien / Köln / Weimar 2002, p. 396-399

Milka Bliznakov: A Life dedicated to the Spiritual in Architecture: Helene Koller-Buchwieser, in International Archive of Women in Architecture, Nr. 8, 1996

Elise Sundt (Hg), Koller-Buchwieser, Helene: in Ziviltechnikerinnen, Eigenverlag, 1982, p. 50f

Archiv der Republik (Staatsarchiv) AT-OeStA/AdR HBbBuT BMfHuW Titel ZivTech H-L 4616, 4928

http://biografia.sabiado.at/koller-buchwieser-helene

https://www.lexikon-provenienzforschung.org

Photo: Portrait Helene Buchwieser 1946, Helene Koller-Buchwieser Papers, Ms1995-020, Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Photo: Projekt Wettbewerb Kirchenneubau Maria Enzersdorf, Südstadt 1968 , Helene Koller-Buchwieser Papers, Ms1995-020, Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Text: Christine Oertel

February 2022